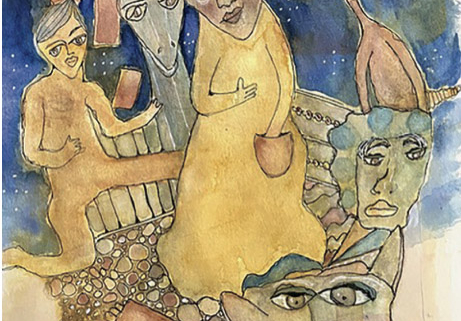

“Holding Her Own,” A story from the upcoming Rooster Princess and Other Tales

Long ago, Rabbi Yeshaya of Poland had a wife, Havva, who gave him constant trouble. She was always praying, morning to night, all day long. She would walk around with her nose in a prayer book, murmuring to herself, not paying attention to anybody else.

After Reb Yeshaya returned home from the synagogue after morning prayers, he would ask, “What’s for breakfast, Havveleh?” only to hear, “Shhh! I’m praying! Don’t interrupt!”

It was no better for him at lunchtime. He would say, as politely as could be, “Dearest, what is for lunch?” to which she’d answer, “Can’t you see I’m busy? I’m in the middle of saying Psalms.”

At dinnertime, when he approached her with, “Havveleh, what have you made for dinner?” She answered, “I can’t make food. I’m not done reciting the holy texts. Please stop disturbing me!”

Later, if he asked for a cup of tea, she said, “You want a cup of tea? You’ll have to make it yourself. I can’t be concerned with physical matters.”

So, naturally, Reb Yeshaya was quite unhappy at home. One day he came to Havva with a book in his hand, pointing to a page. “The sages say right here, ‘What is a good wife? Someone who does her husband’s bidding.’”

She answered him without hesitation. “Really? Well, the sages also say, ‘Whoever is occupied with doing a mitzvah (commandment) is excused from the obligation to perform a different mitzvah.’ And I’m constantly doing a mitzvah—the mitzvah of praying. So, let me be!”

The next day, Reb Yeshaya came back with another book. “Look at this,” he said, “The Torah, in the book of Exodus, says that the pious Jewish women were involved in the building of the Tabernacle in the Sinai. The verse refers to ‘All the women whose hearts were stirred with wisdom.’”

Havva stared at him blankly. “So?”

He continued, gesturing at the page, “So, here, in another section of Esther, it says, ‘All the women should honor their husbands.’ So, the use of this repeated phrase shows that even pious women doing the mitzvah of building the temple were not excused from obeying their husbands’ will and doing their bidding all the time.”

Havva glared at him. “Really? Seriously? You’re quoting me from the book of Esther? Do you think I don’t know the scriptures? That’s the part where King Ahasuerus’s friends convince him to kill his wife, Queen Vashti, because she won’t obey him and dance naked for them! Is that what you want?” She screamed at him, “Do you want to kill me because I won’t do your bidding?”

Reb Yeshaya hollered back, “No! No, I … I don’t want that! I don’t want to kill you.”

“Then what is it that you want?”

He paused and took a breath. “Well, I just … I just want … what I want is to eat, actually. I’m hungry.”

Havva stared back at him, and then she paused. She nodded slowly. “Me too,” she said. “I’m really hungry.”

Reb Yeshaya asked, “Do you think you could show me how to cook an egg?”

She agreed, and they went into the kitchen. While she taught him to cook eggs, they talked about some points of Torah. Then they slowly ate breakfast together.

From then on, they prayed and studied Torah together every day. They discussed each verse, naturally arguing vigorously over every interpretation. And, of course, they began to cook alongside each other each day and enjoyed their hearty meals together. I’m told neither one of them ever went hungry again.

About the story

I encountered this story, called “Standing up for Herself,” in Yitzhak Buxbaum’s Jewish Tales of Holy Women. It ends with the husband admonishing his wife with words of Torah to show her that “pious women … are not exempt from … serving their husbands and doing their will at every hour and time.”

After his version Buxbaum notes, “The tale is told from the man’s side and does not record Rebbitzen Havva’s response to her husband’s final comment. It seems unlikely that she agreed with him; if she had, her submission would have been noted. Perhaps her retort was censored, or she let him have the last word.” In my version, I decided it was time to let her have the last word.

This adaptation is offered with the permission of the Estate of Yitzhak Buxbaum.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!