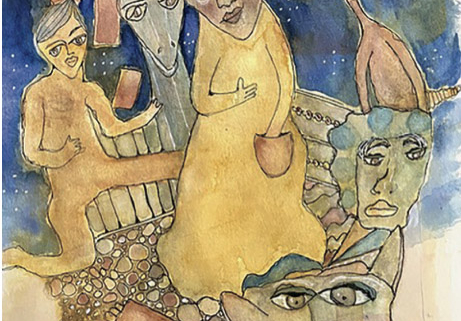

My introductory essay from The Rooster Princess and other Tales.

A few years ago, to stave off boredom at the beginning of the pandemic, I started working on storytelling with my twelve-year-old granddaughter. After she chose a Jewish story to learn, we began to visualize the characters in her story. When asked to describe how she saw Elijah the prophet, she said, without hesitation, “I […]

“Holding Her Own,” A story from the upcoming Rooster Princess and Other Tales

Long ago, Rabbi Yeshaya of Poland had a wife, Havva, who gave him constant trouble. She was always praying, morning to night, all day long. She would walk around with her nose in a prayer book, murmuring to herself, not paying attention to anybody else. After Reb Yeshaya returned home from the synagogue after morning […]

The Confluence

You can spend so long away from the divine that you get hungry. It’s not like hunger in your stomach or thirst in your mouth, but an unnamable itch that gnaws at you until you have to go home. That’s why I went to the cabin each summer. Last summer I arrived there for a […]